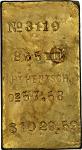

Henry Hentsch Rectangular Gold Ingot. Serial No. 3119. 57.58 Ounces, .865 fine. $1,029.59 Contemporary Value. From the S.S. Central America Treasure.Pristine condition, virtually as issued. Valued at $1,029.59 in 1857 when gold was $20.67 per ounce. Fineness 865.<p>Of the gold ingots found in the <em>S.S. Central America</em> treasure, those of Henry Hentsch are considered among the rarest and most desirable. This is our first offering of an example at auction.<p>Private sales of items from the <em>S.S. Central America</em> began early in 2000. All of the coins and ingots recovered by the Columbus-America Discovery Group were marketed, with 92% of the treasure being handled by the California Gold Marketing Group. The group was headed by Dwight Manley and involved a group of investors including Larry and Ira Goldberg and others, with Q. David Bowers a minor stockholder.<p>The distribution was showcased by the spectacular Ship of Gold display set up across the front of the bourse at the American Numismatic Association Convention in Philadelphia. Tommy Thompson and Bob Evans, the discoverers of the long-lost shipwreck, were on hand to meet and greet visitors. In a separate room as part of the week-long Numismatic Theatre program, Bob Evans gave a presentation, assisted by Dave Bowers. The gallery was filled wall-to-wall with over 400 people - the greatest audience ever for an ANA convention program. Over 20,000 people attended the show - an all-time record.<p>In connection with the offering Dave Bowers wrote the 1051-page, 12-pound, color-illustrated book, <em>A California Gold Rush History Featuring Treasure from the S.S. Central America</em>. The book took Dave about two years to write and involved research ranging from archives in California to the Library of Congress in Washington. No expense was spared to create the finest work possible.<p>When the treasure was marketed there were over 400 gold ingots, mainly of Kellogg & Humbert, and nearly 7,000 coins, including over 5,000 Mint State 1857-S double eagles. Bob Evans was the conservator of the coins and ingots, carefully removing grime without disturbing the original surfaces. He also engaged in research, working with Dwight Manley, and defined the different molds used by the several firms to make ingots and also classified several die varieties of 1857-S double eagles. Assayers who made ingots included Kellogg & Humbert, Blake & Company, Henry Hentsch, Justh & Hunter, and Harris & Marchand, far dominated by Kellogg & Humbert ingots. There were only 33 ingots by Henry Hentsch.<p><strong>Henry Hentsch</strong><p>In his aforementioned book <em>A California Gold Rush History</em>, Q. David Bowers provides the following information on this important California assayer:<p><em>"Henry Hentsch, a Swiss born into a prominent banking family on July 23, 1818, became prominent in San Francisco banking, real estate, and other endeavors, including assaying. In January 1854 he sought adventure and new opportunities, although he was hardly lacking wealth. He sailed for New York on April 5, a passenger on the </em>S.S. Arctic<em>, and on May 5, took the </em>S.S. Illinois<em> from New York to Panama, this being the U.S. Mail Steamship Companys sister vessel with the </em>S.S. George Law<em>, with which its schedule alternated. After connecting at Panama and continuing by steamer in the Pacific, he arrived in San Francisco.</em><p><em>"Soon, he established a small banking office. Already he had extensive experience, having worked with Hentsch & Cie. in Switzerland since 1842. This was published in the </em>Alta California<em>, February 2, 1856 (and other papers):</em><p><em>"ASSAY OFFICE OF HENRY HENTSCH</em><p><em>"Northwest corner of Montgomery and Jackson streets.</em><p><em>"I have this day annexed to my Banking Establishment an Assay Office, and am prepared to carry on this business in all its branches. All orders confided to my care will be executed with promptness, and I will guarantee all my assays,</em><p><em>"H Hentsch</em><p><em>"San Francisco, February 1st, 1856.</em><p><em>"The address was also known as Hentschs Building and Wrights Building. His assay office was annexed to the banking facilities.</em><p><em>"Drawing upon his international connections Hentsch listed references which included Melly, Romilly & Co., Liverpool; Morris, Prevost & Co., London; Coulton & Co., London; Mathieu Hentsch & Co., Paris; and Hentsch & Co., Geneva, Switzerland. As European banks and gold dealers were a major destination for California gold bars, these endorsements no doubt attracted bullion depositors with such customers in mind.</em><p><em>"In 1857 Hentschs bars were probably mainly shipped overseas, including a number placed aboard the </em>S.S. Sonora<em>, August 20, intended for transshipment via Panama to New York City on the </em>S.S. Central America<em>, perhaps then from New York to London, Paris, and Geneva.</em><p><em>"Hentschs business seems to have been successful. In 1858 he was treasurer of the Arrangements Committee (of which Frederick D. Kohler, erstwhile state assayer, was also a member) set up in the city to celebrate on September 27th what was thought to be the successful laying of the Atlantic Submarine Telegraph Cable, linking North America with the British Isles:</em><p><em>"Mr. Henry Hentsch, the treasurer, will receive donations at his banking house, on the corner of Montgomery and Jackson streets, and as it is impossible for the Finance Committee to call upon all personally, it is hoped that those willing to contribute will leave with that gentleman the amount of their subscriptions.</em><p><em>"The banking and assay business continued in good stead. By June 1859 Hentsch was also the official consul for Switzerland, aiding those who had commercial or other interests relating to that country. In the same year he advertised:</em><p><em>"Assay Office and Banking House of Henry Hentsch,</em><p><em>"No. 120 Montgomery Street, San Francisco.</em><p><em>"Assays of Gold, Silver, Quartz, and Sulphuret.</em><p><em>"Returns made in from twelve to twenty-four hours, in coin or bars, at the option of the depositor.</em><p><em>"Charges, one-quarter of one percent, or $3 for lots under $1,200. Bills of exchange on New York, Liverpool, London, Frankfort-on-the-Main, Hamburgh, Berlin, Paris, Geneva.</em><p><em>"Deposits received and general banking business transacted.</em><p><em>"Henry Hentsch.</em><p><em>"Later Years</em><p><em>"In January 1863 advertisements noted that Hentsch and Francis Berton had established Hentsch & Berton, bankers and assayers, now located at 432 Montgomery Street. Listed endorsements suggested that most of its business was with overseas banks and gold dealers, including, as before, Hentsch & Co., Geneva.</em><p><em>"Afterward Hentsch & Berton moved to the southwest corner of Clay and Leidesdorff streets. Throughout the period Hentsch continued to serve as consul to Switzerland. On January 20, 1873, the partnership became the San Francisco branch of the Swiss-American Bank. By that time Henry Hentsch had moved back to Switzerland, where he was in charge of the banks Geneva office, while Berton managed the San Francisco facility. The Swiss-American bank was capitalized at $2 million, with about a quarter of this amount paid in by March 1, 1873."</em><p><strong>Treasure Postscript</strong><p>Years after the recovery of the treasure a second exploration of the wreck of the <em>S.S. Central America</em> was made, this time by Odyssey Marine Exploration of Tampa, Florida. In the summer of 2014, with Bob Evans supervising dives by the Zeus robot, additional coins and ingots were found. These included three small Harris & Marchand bars. The 2014 exploration was quite extensive and likely recovered any remaining ingots, although the future is unknown. Considering the time and expense and likelihood of not much return, no further explorations have been mentioned to us.<p><strong>Reflections on the Gold Rush, the Ship, and the Treasure</strong><p>By Q. David Bowers<p>It seems like only yesterday that I was deep in research about the ship and the Gold Rush, the latter having been a favorite subject of mine for many years. I drew upon information already in print, including in books by Judy Conrad and Normand Klare, in hundreds of contemporary news stories, in material gathered by Bob Evans, and what I and several helpers could find in various libraries. In time I learned so much that I felt that I knew all about the ship and could envision exactly what it would have been like to have been aboard. To tell the story even in condensation would take a hundred pages or more. Here is a short take, so to speak:<p>On August 20, 1857, several hundred passengers boarded the <em>S.S. Sonora</em>, of the Pacific Mail Steamship Line, and left San Francisco headed south toward Panama City. Aboard was over $1.6 million dollars in gold - thousands of freshly minted 1857-S double eagles, some earlier $20 coins, ingots, and gold in other forms. Some of the double eagles were stacked in long rows or columns and nestled in wooden boxes, put under the pursers care. Elsewhere around the ship, passengers had their own treasure-purses and boxes reflecting their success in the land of gold, the new El Dorado.<p>All went well, and in due course the <em>S.S. Sonora</em> landed at Panama City, and the passengers disembarked. The treasure was handled separately and was put aboard a special baggage car on the Panama Railroad, a 48-mile line that had been completed in 1855. Soon, the train arrived in Aspinwall, the passengers alighted, and the treasure was carefully transported to storage.<p>The next leg of the trip was aboard the side wheel steamer <em>S.S. Central America</em>, earlier known as the <em>S.S. George Law</em>, now on its 44th voyage for the Atlantic Mail Steamship Company, commanded by Capt. William Herndon, famous in the naval service including for his explorations of the Amazon River earlier in the decade. In early September 1857, the gold treasure was carefully packed aboard, passengers found their cabins and berths, and all was ready. The steam pressure was raised in the boilers, the paddle wheels started turning, and the <em>S.S. Central America</em> headed out to sea-traveling at about ten miles per hour under sunny skies. After a brief stop in Havana, the ship continued its pleasant voyage on toward New York City.<p>In those days, weather forecasting was not scientific. Little was known about tropical storms, their frequency, and how to predict them, although periodically hurricanes, called equinoctial storms at that time, ravaged that area of the Atlantic, and their danger was well known. However, distinguishing between a gale or small storm and a major hurricane was simply a guess. At 5:30 a.m. on Wednesday, September 9, the ships second officer noted that the ship had gone 286 nautical miles in the preceding 26½ hours, and that there was a fresh breeze kicking up swells. Perhaps a storm was coming. In any event, there was no alarm. This was a large ship, well equipped, and with an experienced crew capable of handling any storm.<p>From here the situation worsened, as the wind intensified, the waves became mountainous, and the ship flooded, extinguishing the fire in the boilers. The <em>Central America</em> wallowed helplessly, her auxiliary sails torn apart, and with leaks pouring water into the hold. By Saturday morning, September 12, 1857, there was no hope. This was not an ordinary tropical storm, and passengers and crew alike feared for their lives. Capt. Herndon ordered the American flag to be flown upside-down as a distress signal. The Atlantic coastal route was well traveled, and surely it would be a short time until other ships came along.<p>Before 8:00 a.m. the ship listed sharply on its side, and many portholes, some broken, were now under water. By 10:00 a.m. the hurricane showed signs of abating. However it seemed that too much damage had already been done to save the ship. Water continued to fill what air spaces remained in the cabins and compartments in the wooden hull, and it seemed that the <em>S.S. Central America</em> had but a short time left. Still, the bucket brigade struggled against the tide, and by the use of hoists and barrels recently emptied of ice-packed pork, the men remaining on the line were able to purge the ship of about 400 gallons per minute. Unfortunately, this was not enough to make a difference. Distress flares and rockets were launched.<p>At about 1:00 p.m. on Saturday afternoon, the sail of the brig <em>Marine</em> was seen on the horizon. This storm-damaged vessel, under the command of Captain Hiram Burt and 10 crew members, drew closer. Aboard the sinking <em>S.S. Central America</em> Captain Herndon ordered women and children on deck, preparatory to boarding lifeboats. The first lifeboat leaving the <em>S.S. Central America</em> was smashed, and other difficulties were experienced as women and children climbed into the small boats. In the coming hours the storm-damaged brig Marine took dozens aboard. Finally, men were allowed into the lifeboats, and a few went over to the <em>Marine</em> including some of the crew of the <em>S.S. Central America</em>, an action that caused many unfavorable comments in later investigations. The <em>Marine</em> eventually drifted several miles away and could no longer render aid.<p>The <em>Central America</em> continued to fill with water. By now, all bailing efforts had ceased, and most of the ship was inundated. Pounding waves broke up cabin walls and floors and tore away sails, spars, and equipment. Some of the men ripped planks and railings off the ship to make crude rafts, while others found single boards. At about 7:50 in the evening, Captain Herndon ordered rockets to be fired downward to signal that the ship was sinking, meanwhile bravely trying to reassure the 438 men remaining on board that other rescue vessels were bound to come along.<p>A few minutes past 8:00 a tremendous wave hit the <em>S.S. Central America</em>. She shuddered, timbers broke, and with hundreds of men huddled at the front of the ship and Captain Herndon on the starboard paddle-box, she slipped at a sharp angle beneath the waves. Many including Herndon went down with the ship, while others clung to wreckage or bobbed about in hollow tin or cork-filled life preservers.<p>Soon thereafter the <em>Central America</em> came to rest in the darkness 7,200 feet below the surface, about 160 miles offshore of Charleston, South Carolina. Passenger gold was scattered here and there around the ships hull and the surrounding sea bottom. In the hold, still stored in the wooden boxes that had been carried along the Pacific Coast by the <em>Sonora</em>, followed by a trip on the Panama Railroad, the treasure of gold coins and ingots remained intact.<p>At final reckoning of the <em>S.S. Central America</em> disaster, about 425 souls were lost. Only 153 were saved.<p>More than a century later, in 1985 a group of entrepreneurs and investors headed by Tommy Thompson and two associates, Robert Evans and Barry Schatz, formed the Columbus-America Discovery Group in Ohio. A ship, the <em>Arctic Discoverer</em>, was outfitted with electronic gear and other devices for exploration, old charts and accounts were studied, and a search commenced. The <em>Nemo</em>, a remote-controlled mini-submarine, was constructed and was equipped with sophisticated instrumentation, lights, cameras, and a grappling device. Of particular note was a mechanism which could dispense a chemical substance at the undersea wreck site. This liquid could surround coins and other objects, harden, and then be retrieved as a solid mass without harming the items encased. Later, the hardened casing could be dissolved, and any encased treasures would be intact.<p>In September 1986 success was theirs, and a hulk believed to be the <em>S.S. Central America</em> was discovered in her watery grave. This proved to be the case. Additional trips to sea were made over a period of time. Finally, thousands of coins and hundreds of ingots were recovered. When the coins were secured on land, news media were contacted and the stories created a sensation. Claimants came from various directions, stating that they had rights based on connections with the original insurers or that they had, in one way or another, helped with the discovery. The matter went through the courts for ten years, involving millions of dollars in legal expenses until the claims were settled. In 1999 the California Gold Marketing Group purchased the interest and rights of the Columbus-America Discovery Group and its investors.<p>What happened afterward is mentioned above. Every time an 1857-S double eagle or an ingot comes my way it brings back great memories. How lucky I and the others have been to have played a part in one of the greatest numismatic scenarios of all time.Ex S.S. Central America.