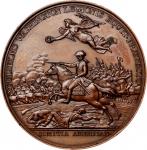

1781 (ca. 1871) John Eager Howard at Cowpens medal. Betts-595, Julian MI-9. Copper. Bell-metal (i.e. “gunmetal”) transfer dies. Philadelphia Mint. 45.0 mm, 758.4 grains. 4.5 - 4.7 mm thick. Choice Mint State.Plain squared edge. An attractive early striking from this first Philadelphia Mint emission of the John Eager Howard type. The surfaces are a deep, rich, even mahogany, with just a glimmer of coppery red visible at the peripheries. The surfaces are particularly nice for a "gunmetal" (i.e. bell-metal) production, glowing and satiny, more lustrous than glossy. The fields show just a few positively minuscule marks, as do the high raised shelf-like rims that give the "gunmetal" issues a distinctively round look. The only marks to note are tiny rim ticks at 12:00 and 6:00 on the reverse, and another above N of LEGIONIS on the obverse. Sholley describes three vertical die lines through the ribbon atop the reverse that designate early die state specimens, and they are easily seen here.<p>According to Julian, the Howard "gunmetal" dies were prepared in 1868, but they dont appear to have been put into use until 1871, when a grand total of three were struck. Five more were struck in 1873, another five in 1874, 10 in 1875, and 13 in 1879. It appears that all Howard medals struck at the Philadelphia Mint after that were coined from newly cut copy dies (as in the final Howard medal here offered) which, despite being engraved REPRODUCTION 1881, werent coined until 1884 at the earliest. Based upon the published records, the total mintage of John Eager Howard medals from the bell-metal dies appears to be just 36 pieces, all in bronze, placing this among the rarest medals struck by the United States Mint. Few have survived in more choice condition than this one.<p><strong>The Philadelphia Mint Comitia Americana Medals from Bell Metal Dies</strong><p><p>Even though coin collecting did not fully blossom into a national hobby until the end of the 1850s, medal collecting had a dedicated following even from the era of the Revolution. Pioneering specialized works on early American medals by Dr. James Mease (1821), J. Francis Fisher (1837), Thomas Wyatt (1848), all preceded Benson J. Lossings popular history <em>A Pictorial Field-Book of the Revolution,</em> which was published serially beginning in 1850 and on its own in 1853. Lossings work introduced many Americans to the Comitia Americana series within their historical context, offering accurate illustrations to would-be collectors who may never have known such things existed otherwise.<p><p>The U.S. Mint began producing medals for sale to a collector clientele by the early 1840s. By 1841, Chief Coiner Franklin Peale had inventoried the medal dies on hand at the Philadelphia Mint, and soon thereafter he began making electrotypes to satisfy collector demand. The August 3, 1844, issue of the Niles Weekly Register, a nationally distributed newspaper, ran the list of medal dies Peale had on hand, which included only Horatio Gates (added to the Mint collection in 1801) and Daniel Morgan (acquired from Paris in 1840) from the Comitia Americana series. But the Mint also offered electrotypes of Washington Before Boston, Anthony Wayne, De Fleury, William Washington, John Eager Howard, Nathanael Greene, and John Paul Jones. The Lee obverse was discovered at some point in the next decade or so, as Mint Director Snowden included it on a list of dies held by the Mint that was published in the Report of the Director of the Mint in 1854. He noted that the reverse was "(Not in the mint)."<p><p>When the large cent series ended in 1857, provoking nostalgia and a newfound interest in saving old coins, an upswell in collector-oriented literature spread word of the world of numismatics all over the country. Local newspapers ran columns and widely-read magazines like Harpers included numismatic content. In 1860, Mint Director James Ross Snowden published a book on the contents of the Mints coin cabinet, then followed that effort a year later with his <em>A Description of the Medals of Washington, of National and Miscellaneous Medals, and of Other Objects of Interest in the Museum of the Mint.</em> Snowdens book offered accurate images of the medals to the Mints growing retail clientele, which seemed to create exactly the byproduct Snowden wished, demand for the Mints most profitable product line: medals.<p><p>It is perhaps no coincidence than the Mint sought to capitalize upon this demand as best they could. The late 1850s and early 1860s saw many new medals added to the Mints list, including several new Washington-related medals (Snowdens pet interest). Cognizant that the U.S. Mint should be able to sell the medals authorized by the Continental Congress, at some point in 1861, James Pollock, the former governor of Pennsylvania who had taken over as Mint Director, wrote to the Paris Mint to request the French government forward the original dies to all American medals they held. The French, understandably, declined, but the Paris Mint was kind enough to sell the anxious Americans 20 specimens each of four medals: the Washington Before Boston, William Washington, John Eager Howard, and John Paul Jones. These medals arrived in Philadelphia in March 1862.<p><p>While a fixed supply was undoubtedly nice to have, Pollock wanted to control the means to produce these medals for the growing legions of new customers. He thus ordered the engraving department to produce new dies, hubbed from the medals newly arrived from Paris. A medal made of relatively soft copper would not work as a hub for a die made of steel, thus a composition softer than copper would need to be used to make the dies.<p><p>These dies have been called the "gunmetal" dies for more than a century, though as numismatist (and metallurgist) Craig Sholley wrote in the August 2018 issue of <em>The Numismatist,</em> the term is a misnomer. Sholley traced the first use of the term "gunmetal" to William Spohn Bakers 1885 <em>Medallic Portrait of Washington</em>. Baker described the first Washington Before Boston medals struck at the Philadelphia Mint and offered this story on their origin:<p><p>This medal furnished at the United States Mint, is struck from gun metal dies made in 1860 from a medal with the second reverse. The manner of making these dies is as follows. The medal is submitted to a heavy pressure from gun metal heated almost into a state of fusion [melting], thus conveying to the metal in intaglio the obverse and reverse of the original piece, and forming dies from which the mint medals are struck. <p><p>As Sholley noted, with this information appearing in no previous publication, it is likely that the Philadelphian Baker received it directly from a friend at the Philadelphia Mint. <p>Sholley dug into the Mint records and found that the Mint had paid John Joseph Charles Smith of Covington, Kentucky $250 in March 1860 for "the right to use his process for impressing dies in bell-metal." Bell-metal was defined in Smiths initial patent application as an alloy of 70% copper with 30% tin, the tin making the alloy softer than the copper that would be used for hubbing. The process placed the soft-metal dies into a "wrought-iron or cast-iron collar" that would keep the pressure of hubbing from completely flattening the dies.<p><p>After the Mint acquired rights to Smiths invention, he innovated further, changing the alloy of the dies to 1/3 copper, 1/3 zinc, and 1/3 antimony. Smith also moved to Philadelphia, apparently to oversee this process. He created a system whereby the soft-metal dies would initially be cast with the design elements, then hubbed for further relief and sharpness of detail.<p><p>Studying the "gunmetal" (i.e. bell metal) productions themselves, this process explains the uniquely textured surfaces, the squared off rims, and the slightly mushy detail compared to the originals.<p><p>In 1863, the Philadelphia Mint prepared new bell metal dies for the Washington Before Boston, William Washington, John Eager Howard, and John Paul Jones medals. These dies did not last long. The dies for the Washington Before Boston medal survived until 1885, striking 145 pieces, the largest mintage of any of the four bell metal die marriages. The William Washington dies also survived well, striking 77 pieces before they were replaced after the 1884/85 fiscal year. Just 50 examples were struck from the John Paul Jones dies before they were replaced by steel copies, 25 struck in 1863 and 25 more in 1868. Only 36 John Eager Howard medals were struck from the bell metal dies, all coined between 1871 and 1879. There exists an extremely rare Howard muling that marries the gunmetal obverse with the new copy reverse; these were likely all or part of the 13 pieces struck in 1879.<p><p>With proper study, the bell metal Comitia Americana medals become easy to discern from Paris Mint strikes or later copies. Medals struck at the Paris Mint after 1842 all have edge markings, so those are easy to identify. Those struck before 1842 (usually termed "originals") have distinctively reflective surfaces that are always smooth, relatively thin planchets, edges that are either concave or gently rounded at the rims, and incredibly crisply struck detail. The later Philadelphia Mint strikes from copy dies show typefaces that are very different from those seen on the Paris Mint dies and their bell metal copies, even though the central design elements are more or less the same. Since the designs of the bell metal copies are essentially the same as their Paris Mint progenitors, texture and style tells the story: surfaces that are glossy at best or even matte, but never reflective; an applied bronzed patina, usually mahogany in color, that is unlike any ever used in Paris; a very square edge, usually significantly thicker than that seen on Paris Mint strikes, and mushy fine details that are especially lacking in sharpness at their peripheries. The bell metal strikes are often slightly smaller in diameter than the Paris Mint originals as well.<p><p>The Philadelphia Mint bell metal Comitia Americana series is short - just four medals - but is an important chapter in the series. They are the first examples of those four medals ever struck in the United States. They were coined just as medal collecting became central to American numismatics and, more broadly, one of Americas most popular hobbies. Their mintages are tiny, far smaller than Paris Mint restrikes or even Paris Mint originals, but their value in the marketplace has not yet caught up to their rarity. Had the Julian book given them different numbers than the later copy dies (they are entirely different medals, after all), the collector market for them might be far different. When the Julian masterwork that has guided this part of the hobby for decades gets updated, this would be a vital edit that could extend the life of that reference for another century.<p><p><strong>The Battle of Cowpens</strong><p><strong>The Action:</strong><p>The day after Christmas 1779, Sir Henry Clinton and General Charles Cornwallis left British-occupied New York with more than 8,000 men. Their destination was Charleston, South Carolina, and upon their arrival the focus of the Revolutionary War became the struggle to win the hearts, minds, and battlefields of the Carolinas. Clinton and Cornwallis laid siege to Charleston beginning in April 1780, and the following month they controlled the city. Their army made its way to the middle of South Carolina and encamped near the town of Camden, where Horatio Gates, the newly appointed commander of the Southern Department, encountered Cornwallis force in August 1780. Gates was soundly defeated, his force decimated, his reputation essentially destroyed. Cornwallis and his forces, including reviled Banastre Tarleton, captured the tiny hamlet of Charlotte soon thereafter, then made their way back to winter camp in central South Carolina, in the town of Winnsborough.<p>Following Gates relief from command, General George Washington dispatched a member of his "military family" to the Southern Department: Nathanael Greene. Greenes strategy revolved not around direct large-scale confrontation, but fleeting contact and costly chases, meant to expose the British and their Loyalist partisans to guerrilla attacks and keep their divided forces far from supply lines. The October 1780 American victory at Kings Mountain, along the North Carolina / South Carolina border, bolstered the Patriot cause in the Upcountry. Greene had made his winter camp in Cheraw, in the eastern Pee Dee region of South Carolina, but a portion of his troops under General Daniel Morgan continued to move through the backcountry. Cornwallis dispatched Tarleton to give chase with a force of just over 1,000 men, mostly British regulars.<p>Morgan chose the place he would permit Tarleton to meet his men: at the Cowpens, a pasture near the North Carolina state line close to modern Spartanburg. Morgan, known for his team of crack riflemen, decided to capitalize upon the British stereotype that American militiamen would quickly retreat. He ordered his militia to do just that, then move to the rear, reform, and wait for Continental regulars to break through the British line.<p>Holding the rear high ground, his plan worked like a charm, finished off by an infantry line held together by Col. John Eager Howards leadership and a cavalry charge led by Col. William Washington as the denouement. Morgan described his defeat of Tarleton as "a devil of a whipping." Congress agreed, and selected him to receive a gold medal, while both Howard and Washington were awarded silver medals. Only Cowpens and the 1779 reduction of Stony Point were recognized with three medals. <p>After the victory at Cowpens, Greene and Morgan reunited and moved north, meeting Cornwallis at Guilford Court House in March 1781. With his force badly weakened after the battle, Cornwallis marched for Wilmington, on the North Carolina coast, to regroup. His next, and final, stop would be Yorktown.<p><strong>The Resolution:</strong><p><em>The United States in Congress assembled, considering it as a tribute due to distinguished merit to give a public approbation of the conduct of Brigadier General Morgan, and of the officers and men under his command, on the 17th day of January last; when with eighty cavalry, and two hundred and thirty-seven infantry of the troops of the United States, and five hundred and fifty-three militia from the States of Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia, he obtained a complete and important victory over a select and well appointed detachment of more than eleven hundred British troops, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Tarleton; do therefore resolve,</em><p><em>That the thanks of the United States in Congress assembled, be given to Brigadier General Morgan, and the officers and men under his command, for their fortitude and good conduct, displayed in the action at the Cowpens, in the State of South Carolina, on the 17th of January last:</em><p><em>That a Medal of Gold be presented to Brigr Genl Morgan representing on one side the action aforesaid particularising his numbers, the numbers of the enemy, the numbers of killed, wounded and prisoners and his trophies with the inscription patria virtusis [undecipherable], and on the other side his bust with his name and this inscription: Ipse agmen the figure of the General on horseback leading on his troops in pursuit of the flying enemy, with this motto in the Exergue Fortus Fortuna Juvat Virtus Unita Valet.</em><p><p><em>That a medal of gold be presented to Brigadier General Morgan, and a medal of silver to Lieutenant Colonel W. Washington, of the cavalry, and one of silver to Lieutenant Colonel Howard, of the infantry of the United States; severally with emblems and mottos descriptive of the conduct of those officers respectively on that memorable day:</em><p><em>That a sword be presented to Colonel Pickens, of the militia, in testimony of his spirited decisive and magnanimous conduct in the action before mentioned:</em><p><em>Resolved, that a sword be presented to Lieutenant Colonel Howard of the infantry, and one also to Lieutenant Colonel Washington of Recommitted. the Cavalry of the federal army each, that their names may be transmitted honourably to posterity renowned for public virtue and as testimonies of the high sense entertained by Congress of their martial accomplishments.</em><p><em>That Major Edward Giles, aid-de-camp of Brigadier General Morgan, have the brevet commission of a major; and that Baron de Glasbeech, who served with Brigadier General Morgan as a volunteer, have the brevet commission of captain in the army of the United States; in consideration of their merit and services.</em><p><em>Ordered, That the commanding officer in the southern department, communicate these resolutions in general orders.</em><p><em>- Continental Congress Resolution of March 9, 1781</em><p><strong>John Eager Howard at Cowpens</strong><p><strong>The Acquisition: </strong><p>Along with the William Washington medal for Cowpens, and General George Washingtons medal for the action at Dorchester Heights, this was among the very last batch of Comitia Americana medals completed. David Humphreys handed the Comitia Americana project off to Thomas Jefferson in an April 4, 1786 letter: "I have made no contracts for the other four, viz. for Genl. Washingtons on the evacuation of Boston, for Morgan, Washington and Howard on the affair of the Cowpens, because the designs for them have not been in readiness for execution until the present time." Jefferson hired Pierre-Simon-Benjamin Duvivier to do all three of those mentioned; the fourth commission, for the Daniel Morgan medal, went to Augustin Dupre, who Jefferson preferred as the superior artist. Jeffersons initial contact with Duvivier appears to have come no earlier than the end of 1788, more than two and a half years after Humphreys departure. Duvivier wrote to Jefferson four times in 1789: on January 5, February 23, April 11, and June 7. None of the letters have survived. But when Jefferson boarded a ship bound for Norfolk, Virginia in the fall of 1789, he carried with him all of Duviviers works, including the silver medal for Howard.<p><strong>The Presentation:</strong><p>Jefferson turned Howards medal over to Washington in March 1790, along with Washingtons set of silver Comitia Americana medals and the unique Washington Before Boston medal in gold, as well as other medals bound for their Congressionally authorized recipients. Washington tucked Howards silver medal into a letter dated March 25, 1790 and dispatched it by mail.<p><em>New York March 25th 1790</em><p><em>Sir,</em><p><em>You will receive with this a Medal struck by order of the late Congress in commemoration of your much approved conduct in the battle of the Cowpens-and presented to you as a mark of the high sense which your Country entertains of your services on that occasion.</em><p><em>This Medal was put into my hands by Mr Jefferson; and it is with singular pleasure that I now transmit it to you.</em><p><em>I am, with very great esteem, </em><p><em>Your Excellencys most Obedt Servt</em><p><em>Go: Washington</em><p>Howard responded with the enthusiasm his military bearing could permit on June 21, 1790, from his home in Annapolis. <p><em>Sir,</em><p><em>I had the honor to receive your Excellencys letter of the 25th march with a medal ordered to be struck by the late Congress. my only object in the late war was to render any service in my power in the common cause, and my only hope of reward was that my conduct might meet the approbation of my Country; the obliging manner in which you are pleased to communicate this mark of approbation which my Country has expressed of my conduct, affords me the highest satisfaction.</em><p><strong>The John Eager Howard at Cowpens Medal:</strong><p><strong>Obverse:</strong> As Col. Howard charges right with sword drawn, Victory reaches up to crown him with a laurel with her right hand and holds up a palm branch with her left. A British soldier carries his flag and runs off to the right, leaving his sword and tricorn hat behind. JOH EGAR HOWARD LEGIONIS PEDITUM PRAEFECTO means "John Eager Howard, who commanded the cavalry regiment." COMITIA AMERICANA is seen in the exergue below. Howards actual middle name is Eager, not Egar, as spelled on the medal. The original draft of the Congressional resolution called for the obverse to show "the charge ordered and conducted by him in that critical moment when the enemy were thrown into disorder by the fire from the line under his Command, and the latter instantly charging, victory hovering over both Armies and dropping a branch of Laurel to be instantly snatched by Lt. Colonel Howard, with this Motto- occasione oerupta."<p><strong>Reverse:</strong> An unending wreath of laurel, festooned with internal ribbons at top and bottom, surrounds a seven-line legend: QUOD IN NUTANTEM HOSTIUM ACIEM SUBITO IRRUENS PRAECLARUM BELLICAE VIRTUTIS SPECIMEN DEDIT IN PUGNA AD COWPENS XVII JAN. MDCCLXXXI (By his impromptu charge at the enemys wavering line, he showed an example of bravery in battle at Cowpens, January 17, 1781). This is an improvement upon Congress proposed inscription: "In honor of the prompt and decisive conduct and gallantry of Lt Col Howard in the action of the victory obtained at the Cowpens 17th of January 1781."<p><p><p>From the John W. Adams Collection.